Alina B. López Hernández

Imposed Social Agendas or Outstanding Debts?

Anyone who uses social networks and digital media will find that in Cuba, the trends of the debate about civil society display some recurring themes: racial discrimination, feminist demands, the struggle for rights of the LGBTI community, oppositional artistic projects, and protections for animals and the environment. Some converge and others march separately; as a whole, they could be conventionally defined as a “public agenda,” although they lack the organization and joint planning characterized by the term.

The Cuban government perceives these demands, and especially the activism they generate, as infringements by external entities trying to subvert and change the regime.[1] It is not illogical to think that disagreements on these issues can foster internal political discrepancies; however, accepting this thesis does not help explain the popularity these movements enjoy today. In order to do so, two fundamental aspects must be taken into account: 1) Cuba’s internal conflicts with respect to these issues, which have its roots in the final years of the sixties, and 2) their resurgence dating back to the nineties, motivated by the fall of socialism and its resulting economic and ideological conflicts. But, the fact that their current prominence is driven by greater access to the internet and social networks should mislead us. When was the road lost? When were these sensitive topics revisited again? This article sets out to answer such questions, but does not pretend to characterize the multiple movements, projects, activists, or platforms that exist in the digital media ecosystem.

The Lag

In the late 1960s, the world was awash in Cultural Revolutions.[2] The French protests of May 1968 led a movement against all kinds of authoritarianism and hierarchies: familial, social, artistic, and educational. Young people challenged the values of their parents and opposed a corseted and conventional society. They criticized elitism, bureaucracy, bourgeois morality, Soviet Marxism, the state, and militarism.

These youth and countercultural movements were atomized into multiple groups, representative of the social fringes that sometimes intersected: pacifists, feminists, homosexuals, ecologists, different tendencies of modern art; even in Czechoslovakia, they advocated for “socialism with a human face.”

Directed towards the cultural and ideological, these struggles were seen on the streets, classrooms and university campuses, concerts, and camping trips. The movements resonated on all continents and in all countries, although not equally, and their relative failure did not undermine the impetus they gave in subsequent years to the feminist cause, to the historical struggle for the rights of minorities and inferior racial groups, and to early environmentalism.

Such events in Cuba coincided with a period of radicalized socialism. The Cuban Revolution achieved a popular consensus with widely accepted measures which included: equal and free access to education, basic levels of nutrition, a public health system unthinkable for a third world country, and diverse cultural options.

To the same extent that it benefited the majority, it required unconditionality. Unanimity was carved as a monument—especially after 1965, the year the Cuban Communist Party was established as the country’s single Party. The early control of the press by the government made it possible to direct public opinion.

The aspiration to build a communist society took hold in 1968 with the Revolutionary Offensive, which liquidated small, and even smaller, private property—a decision that would take decades to reconsider and has never been admitted as wrong.

In the artistic field, controversy was generated by the poetry collection Fuera de Juego, by Heberto Padilla, and by the play Los siete contra Tebas, by Antón Arrufat. A significant symptom of the direction taken by cultural policy, which was controlled by the Party’s ideological apparatus, would reach its maximum expression three years later with the agreements of the First Congress on Education and Culture.

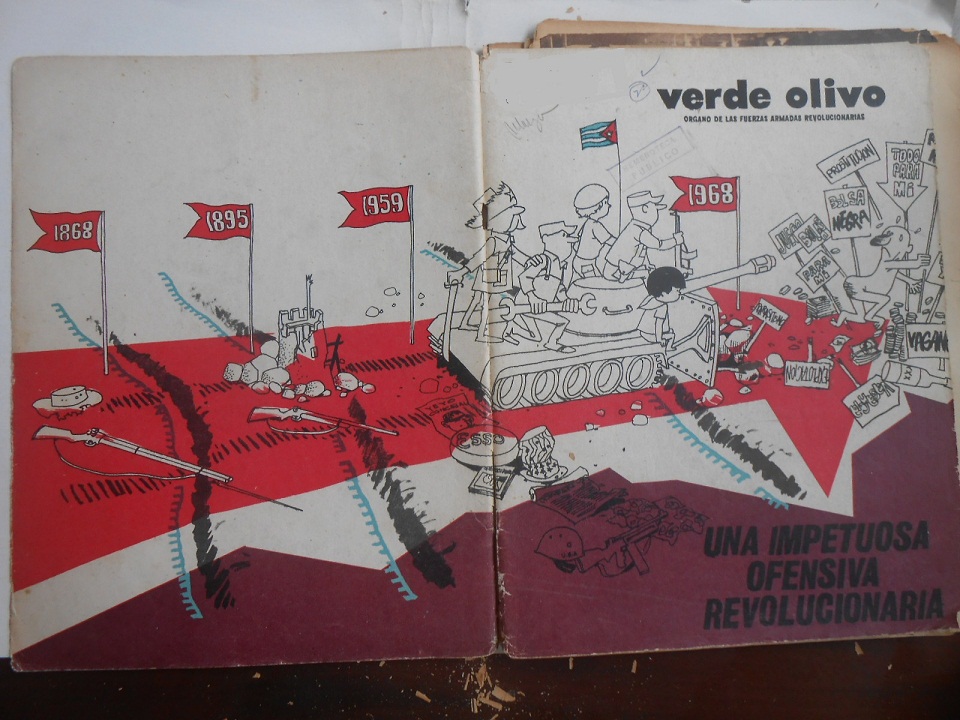

There was an interesting, symbolic appropriation of the centenary celebration of the wars for independence. The Revolution was ruled as a unique process with a genesis in 1868, but which intrinsically included socialism, considered a milestone in 1968. This idea is conveyed by the cover of the Verde Olivo magazine corresponding to April 7th, 1968, even before Fidel’s well-known speech on October 10th in which he proclaimed said thesis.

As the definition and limitations of “revolutionary” were tightened, civil society was reduced. This was obviously influenced by the prohibition of associations other than those authorized by the government.

At a time when the Cultural Revolution in China became a protagonist of world events, with its opposition to bureaucracy, verticalisms, tradition, and authoritarianism; an antithetical discourse was building strength in Cuba since it demonized everything that deviated from the norm. At that stage we were, more than ever, an island.[3]

It was utopic to think that racism would be abolished immediately by egalitarian policies applied from the start, since they benefitted black and mestizo people as part of the common good. It was also not a good time for feminism or for homosexuals. It was not good for anyone who tried to stand out from the social body. We coexisted as a gigantic majority.

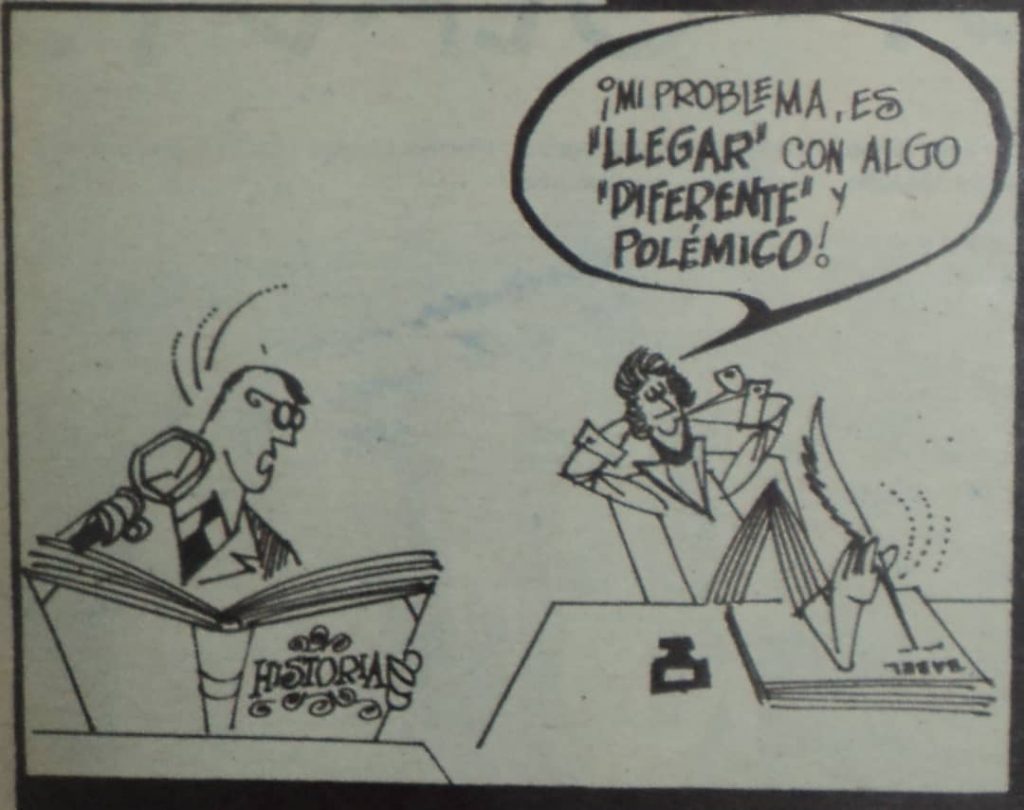

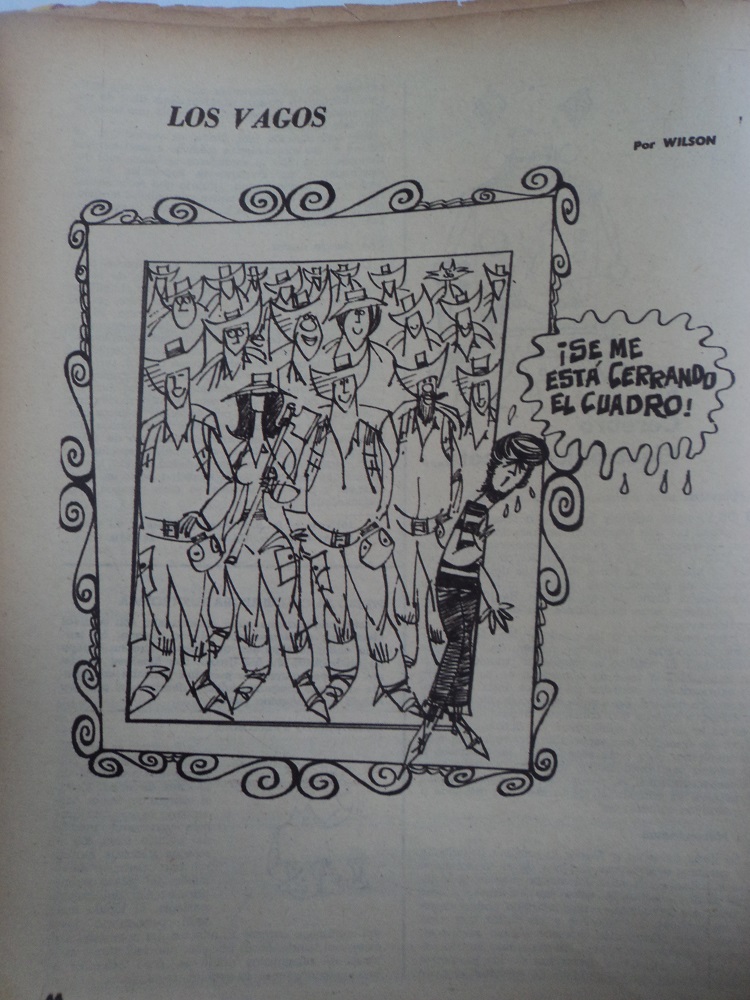

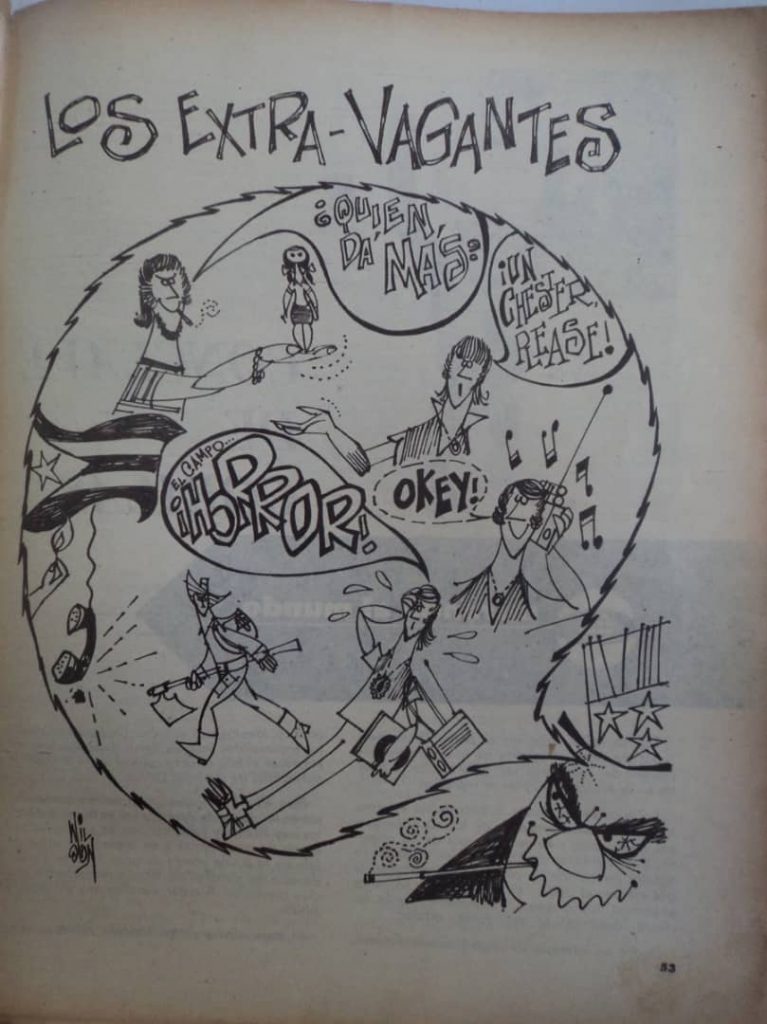

The predilection for a monolithic, standardized, and obedient society can be seen in the following cartoons:[4]

The first, “Musa snob,” makes it clear at a textual level that the different is not good; this idea is reinforced in the image where the culprit of controversy is dressed informally, has long hair, and is carefree. His attitude contradicts the dapper figure with necktie and noticeably short hair reading a history book, shown (by coincidence?) on the left. He looks amazed, annoyed, and simply reads on.

The second, “Los vagos,” presents a standardized image of a public. Similar looking people fill the picture. They dress the same way, resembling an army, and smile. There is no room for the only one who looks different.

In the third, “Los extravegantes,” a worker turns his back on figures with long hair, different costumes, and who enjoy music and the English language—they represent what is “alien” and are consenting of imperialism. They are antagonistic to the nation, as indicated by the flag about to be burned.

These cartoons did nothing more than confirm/reaffirm the policy of intolerance that was already in place. The Military Production Support Units (UMAP) functioned from 1965 to 1968. They were camps located in the province of Camagüey, where men who were considered outside the revolutionary norm were confined: homosexuals, religious men, common prisoners, long-haired young men, and rock n’ roll lovers. Testimonies from those at the camps, or their families[5], show that they were subjected, for re-educational purposes, to methods ranging from psychological pressure to physical torture. No one has ever taken responsibility for what happened to them or apologized to those affected.

The article “Primavera de Praga-Verano en La Habana” reveals aspects of that period reflected in the press.[6] In addition to the Ofensiva Revolucionaria, the internal news focused on the coffee belt around Havana, as well as the preparation needed for the production of ten million tons of sugar two years later that would earn us the capital to industrialize ourselves. The external news emphasized the struggles of African Americans for their rights—comparing them to the achievements on the island—and on the condemnation of the war in Vietnam. A prominent part of the news reflected daily life in socialist countries, from fashion to the use of free time, as well as political and economic achievements.

We must constantly return to the decade of the sixties to talk about the lost opportunities in economic, political, and ideological development,. There was a drive to build a national, socialist project, which acquired early on a dogmatic ideology but was still confronted by critical leftist tendencies, that later failed due to enormous errors and aggravations by external pressures.

Due to the failure of the 1970 harvest, Cuba adopted a model of socialism that was administratively and ideo-politically similar to the Soviet one. Unanimity, intransigence to differences, and the cult of dogmatism would be its defining attributes.

The call to shape the “new man” was the aspiration of the educational system, which reproduced intolerance thanks to its behaviorist and authoritarian model; for its part, the Quinquenio Gris from 1971 to 1976 was characterized by dogmatism in the cultural sphere, limitations of intellectual freedom, and the enthronement of socialist realism as a method of creation.

Homosexuals and the religiously devout were discriminated against and could not work in sectors such as teaching, culture, or public relations. After the creation of the Ministry of Culture in 1976, some of the irrationality was corrected. However, in the educational sector of the early 1980s, being effeminate could cost one their job or the opportunity to study. It would not be until 1988, with the creation of the National Center for Sexual Education, that the study of sexuality would be updated and a respect for orientation promoted.

Within the feminine sphere, despite the many benefits that the revolutionary process provided—scholarships, jobs, support for raising children, equal pay, etc.—we lagged in concepts and discourse. It did not have the theoretical tools of gender, which made it possible to hide serious problems such as psychological and physical abuse, and even feminicide, disguised under the euphemism “crimes of passion.” The Mariel exodus left many women as head of their household, a situation that was later reinforced by high divorce rates.

Regarding racism, the lack of research and debate was such that the political scientist Jorge Domínguez called it a “non-issue” in Cuban studies.[7]

The End of Utopia, but Not of History

In the winter of 1991, the USSR witnessed 74 years of socialism come to a not so happy end. The rest of the socialist bloc had preceded it. Cuba, which was economically dependent on them, stopped receiving oil, and lost its largest sugar buyer, 85% of its commercial exchanges, and a steady supply of technologies. The crisis was brutal. It was called the “Special Period”—a noble epithet for what we lived.

Some sectors were more vulnerable because they were not related to any of the new sources of income: tourism, small businesses, or remittances. Poverty levels and inequalities increased. We were no longer the homogenized and smiling group that the cartoon showed. The creation of careers in sociology during those years revealed the government’s concerns.

Among the most disadvantaged were black people, who are historically disadvantaged because they do not own, with few exceptions, long-standing heritage, large and luxurious mansions, or other properties that could be used for business. Racism presented obstacles to accessing the private sector, which have higher paying jobs.

The historian Alejandro de la Fuente draws attention to a significant fact of the past year: while 58% of Whites have an annual income below $3,000, among Blacks that proportion reaches 95%. In addition, they receive a limited part of family remittances. [8]

In the 1990s, the non-topic would become relevant and allow for the articulation of a movement that included Black intellectuals, filmmakers, artists and musicians, and more recently bloggers, independent journalists, activists, and cultural promoters.[9]

Another vulnerable group were women. At the beginning of the nineties, a pioneering feminist organization called Magín emerged, but was forced to disband in 1996 due to intolerance by political authorities. The 2015 book, Magín, Time to tell a story, written by Daisy Rubiera and Sonnia Moro, explains:

In those years, the worst of the economic crisis was experienced […] many [women] left their jobs and returned home; some put off forever the desire to have children; a great majority drew strength and creativity from where there seemingly was none, almost in an act of magic and inventiveness, to support the hygiene, health, and life of their family nucleus. Some emigrated, others stayed, some prostituted themselves, and the vast majority resisted the blow of the crisis for themselves and their loved ones. Almost all of Cuba moved by bicycle, made its own soaps, innovated culinary techniques, juggled electrical blackouts, and lived with the bare minimum.

Women tend to experience the consequences of shocks more quickly, and the benefits of recovery more slowly, as found in a study by researcher and activist Ailynn Torres Santana in OnCuba.[10] However, the FMC, a non-feminist women’s organization, prioritized the defense of revolutionary conquests through the iron unity of the Cubans, an attitude that made the specific needs and aspirations of women invisible. The disbanding of Magín interrupted the feminist experience for several years, which has resurged in recent times, because the problems became acute after being neglected.

Today we are owed laws that protect against gender discrimination, allow equal marriage, and protective the rights of animals, along with many others. Last March, a government commission was created to lead the National Program Against Racism and Racial Discrimination, but its concrete actions are still unknown.

The late arrival of the Internet to Cuba coincided with such an accumulation of debt in these matters, that we do not even have to blame external forces. Today we live out our cultural revolution energetically because it has been delayed for too long. Like the sixties, it takes place outside of traditional institutions of political and social participation, parties, or unions, which in Cuba are formal and have lost their leadership.

Now social networks and alternative media, with their lights and shadows, are becoming a platform for claiming rights. They not only offer an alternative to a civil society limited by prohibitions, but they also make visible multiple deficiencies. The roads that were lost on these issues 52 years ago are being traveled today, but the speed of the race is supersonic because the digital age begets immediacy.

A challenge remains before us: understanding that the struggle for the rights of social sectors and minorities must go hand in hand with pressures for political transformation. That will lead to a democratization of socialism and citizen participation. But, that analysis exceeds the scope of this article.

Alina B. López Hernández is a teacher, essayist, editor, PhD in Philosophical Sciences, and corresponding Member of the Academy of History of Cuba.

[1] See articles “¿Una contrarrevolución preferible?” http://www.cubadebate.cu/especiales/2020/05/30/una-contrarrevolucion-preferible/ and “Revictimizada mil veces” Granma 18/7/2020, by Javier Gómez Sánchez.

[2] N.E. – the author refers to these movements: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Movimientos_sociales_de_1968

[3] https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/06/04/opinion/1528129217_246327.html

[4] Appeared in Verde Olivo magazine, on the dates: 27/10/68, p. 13; 07/04/68, p. 44 y 06/10/68, p. 53.

[5] Alberto I. González: Dios no entra en mi oficina, CreateSpace. Independent Publishing Platform, 2012; Carolina de la Torre: Benjamín. Cuando morir era más sensato que esperar, Editorial Verbum, 2018; Raimundo García Franco: Llanura de sombras. Diario de un pastor en las UMAP, Christian Center for Reflection and Dialogue-Cuba, 2019.

[6] Javiher Gutiérrez and Janet Iglesias, Fernando Ortiz Center for Higher Studies, University of Havana, (unpublished).

[7] José I. Domínguez: “Racial and Ethnic Relations in the Cuban Armed Forces. A Non-Topic” in Armed Forces and Society, no. 2, 2/1976, pp. 273-290.

[8] “Cuba hoy: la pugna entre el racismo y la inclusión,” https://www.nytimes.com/es/2019/04/26/cuba-racismo-afrocubanos/

[9] Alejandro de la Fuente analyzes it in: “Tengo una raza oscura y discriminada: El movimiento afrocubano: hacia un programa consensuado.”

[10] “The ‘Special Period’ of Women in Cuba”

BACK TO NUEVOS ESPACIOS