Ricardo Torres

Cuba Must Not Wait to Unleash the Potential of its Workforce

The most intense debates taking place in Cuba revolve around economic reforms and possible pathways for development. This justifies any effort to figure out the essence of the challenge posed before the Cuban society. The problems and their solutions are not limited to the economic field. But these issues have such an impact on the material and spiritual lives of people, that they easily draw a lot of attention. Everyone knows that decisions made today will alter the political equilibrium and position of this small Island before the world. This article seeks to contribute to the analysis of economic perspectives of our country by setting aside the mantra which expresses a certain national preference for the tragic narratives of the history.

Domestic resources for Cuba’s development

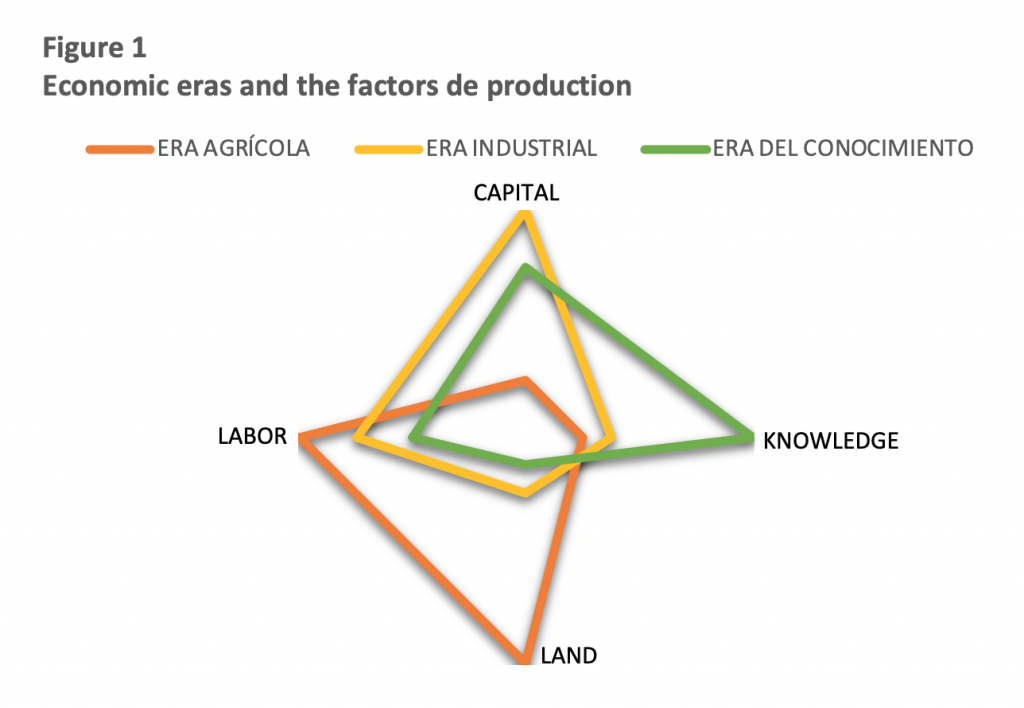

Economic models are transcendental for guiding the development efforts of a country during any era. During the agricultural period, the population and availability of land were crucial elements which made possible the development of civilizations. Later, the Industrial Revolution changed the focus to physical capital, more specifically to machinery, and transportation systems necessary to link growing production with the consumers. In recent decades, we have witnessed a movement towards a productivity model in which the education of the labor force, and information and communications technologies (ICTs) are more prominent. (Figure 1). It has been estimated that between 1995 to 2012, half of U.S. economic growth was related to skilled work and ICT capital (Jorgenson, 2018). This does not imply that all countries advance at the same rate. Nor is progress is automatic or spontaneous. But adapting to this shift is crucial precisely because scientific and technological development are driving the most dynamic sectors of the modern economy.

Taking into account its land endowments (0.64 acres per inhabitant) and natural resources, we can say that Cuba is relatively poor. The acquisition of rents remains consistent with investments, and its products can’t count on dynamic markets. Consider sugar or nickel as examples. Furthermore, the meager level of investment in, and continual expansion of, the labor force result in very low levels of physical capital per worker. Repurposing that human capital would be far more promising.

“Cuba possesses all the essential components to become a health and wellness hub…Of course, this requires different type of organizations than the ones we have, and workers motivated by other incentive structures.”

According to the U.N.’s Human Development Index, Cuba’s educational attainment achieved is close to 80%—above the average of other countries in the region and countries with similar income levels. However, there are conflicting ways to interpret these results. A favorable view is that this success was achieved in spite of Cuba being a poor country. A more pessimistic interpretation suggests that the country has not been able to capitalize on these results to improve its economic performance and the living standard of its people.

The unlocking of this potential faces multiple obstacles present in any development strategy. To put its human talent to use, Cuba must have access to hardware, which in the 21st century consists of ICT systems and digital infrastructure. Internet is to this century what electricity was at the beginning of the 20th. As a famous economist once said: “it is impossible to make a good programmer without a computer.” There has to be some level of correspondence between human talent and the physical capital it needs to be truly productive.

This balance cannot be achieved through abstractions. Not all activities utilize human capital equally. That is why dynamic economies are those which are able to allocate a growing part of their labor force to dynamic sectors which make more intensive use of knowledge. This not only refers to technical skills. It is just as important to invent a new process as it is to commercialize it efficiently. In this, there is a remarkable gap in Cuba. Under a different approach to development, the export of medical services could enhance its scope beyond the mere sending of professionals, by means of contracts with a high degree of standardization and buoyed by relations with the destination country. Cuba possesses all the essential components to become a health and wellness hub. Our international tourism industry should aim beyond just the sun, beaches and all-inclusive hotels; and highlight other unique characteristics, such as our art, history, and nature. In that regard, the salaries of workers cease to be a cost and instead become a basis of differentiation. Of course, this requires different type of organizations than the ones we have, and workers motivated by other incentive structures. The productive transformation of an economy depends on the instructions provided by its software, meaning its economic model.

Reforming the economic model

The notion that Cuba’s future development depends on the profound reform of its economic model is not new. In fact, the launch of what was called the “actualización” (“updating”) confirms that even the authorities recognized the presence of systemic weaknesses that are incompatible with our long-term economic sustainability. What we have yet to achieve is a consensus on the steps needed to implement the changes, which are neither minor nor easy.

In general, a centrally-planned economic model combines two interrelated characteristics. On the one hand, the overwhelming majority of the means of production are managed by state-owned companies. On the other, the central allocation of factors and resources by a public entity substitutes the pricing system as the principal mechanism for coordination. This property system was considered to be the basis for a new society, one of social justice. Yet with the passing of time, this way of organizing production posed undeniable challenges. The dominance of state-owned property creates perverse incentives in enterprise management which discourage the search for efficiency and innovation (Kornai, 2014). At the same time, efforts to substitute the pricing function with administrative edicts and mobilizations create serious distortions in economic management.

“Since development is essentially a home-grown process, Cuba should start by fixing its own internal inequities. Relying on a favorable outcome in the upcoming U.S. election or the geopolitical whims of great powers to improve our outlook is a dangerous illusion…”

These practices cause serious contradictions that affect Cuba’s political economy as well as its policymakers. The poor performance of state enterprises leads to a lack of resources to meet the requirements of a hypertrophic “welfare state. Nor has social policy been sufficiently modified to serve a more heterogeneous and fragmented socio-economic structure. The tension between needs and resources leads to sub-optimal levels of productive investment, which feeds into slow cycles of growth and low productivity. The solution is not to be found in reducing social spending but in increasing the effectiveness of firms. On the other hand, pressures to generate new resources and income combined with the uncertainty inherent to market relations, lead to the search for contracting partners who could offer favorable terms. These provide a significant source of income which enables the postponement of changes considered taboo on the Island. Lastly, the difficulties of linking an economy like ours to other markets required the implementation of an impossible system: a sui géneris system of monetary and currency exchange. Since 1993, officials have tried to make this system work to no avail, and the resulting distortions have been so severe that, at the end of 2019, we are once again heading down the road of partial[ institutional re-dollarization.

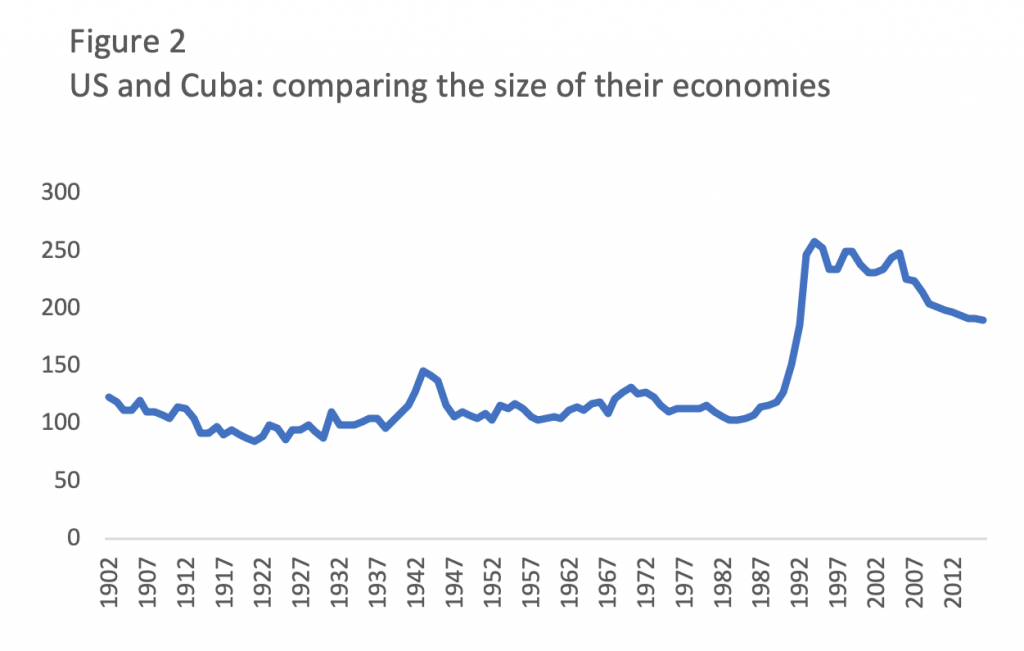

On relations with the United States

No country is an island, economically speaking. At the very last, we can never ascertain whether economic trajectories are exclusively the result of domestic policies. Invoking the strained relationship with the United States in order to justify internal evils or framing it as the only cause of these evils, is old hat in the history of Cuba. The United States has always been Cuba’s most important neighbor, but it has experienced enormous transformations during the past 200 years. The existence of a remarkable asymmetry in economic power is well known, even if it is poorly documented. This asymmetry has always served the interests of the United States, which has used it to impose certain decisions on its neighbors, not only on Cuba. The dimensions of this imbalance are overwhelming, even though the numbers have not always remained the same, as shown in Figure 2. These dynamics help us understand many developments of the 20th century.

As Cuba entered the second half of the 19th century, the gap widened. The country which intervened in the Spanish-American War had an economy 124 times larger than Cuba’s, the latter of which, to be fair, was devastated by the war. During the 20th century, the gap between the two economies fluctuated, but always remained large. The widest point came after 1985, when a profound economic crisis devastated the Island due to internal deficiencies, which we tried to mend with the Rectification of Mistakes and Negative Tendencies Process (Proceso de Rectificacion de Errores y Tendencias Negativas), followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Council for Mutual Economic Aid (CAME). From that year on, the economic asymmetry more than doubled. Add to this another important element: the origin of a liberal unipolar international order in which the United States emerged as the indisputable leader (Mearsheimer, 2019).

Models that try to explain bilateral trade highlight two fundamental variables: size and proximity. In the case of Cuba, this means that the United States would be its natural trade partner since it amply complies with both conditions. The productive output of both countries shows a high level of complementarity. Each one produces and exports goods and services that the other buys in large quantities.

Combining this economic asymmetry with the privileged position of the United States in Cuba’s international trade relations helps us understand the contemporaneous factors that greatly influence Cuban development. First, inaccessibility to the American market means a substantial increase in costs for Cuban foreign trade, regardless of its access to other markets. A partial compensation of these immense costs can only be achieved if other markets could open to Cuba under preferential conditions. This is not always possible due to the internal commitments of governments and has been proved to be unsustainable in the long term. Because of its huge size, finding a substitute for the United States is not easy. Its importance is magnified by its technological superiority, its position as the axis of the postwar international order, and its community of Cuban immigrants.

Secondly, this asymmetry provides U.S. administrations with plenty of leeway to impose sanctions, due to the marginal impact these have on its domestic economy. At the same time, its internal political agendas discourage the lifting of these sanctions. It is true that U.S. hegemony is now being challenged by China. But it will take decades before China can claim supremacy in all important fields, and it would still remain a geographically distant partner for the Island.

What can be done?

Our analysis leaves us with some certainties about possible alternatives and brings order to the sequence of implementation. Since development is essentially a home-grown process, Cuba should start by fixing its own internal inequities. Relying on a favorable outcome in the upcoming U.S. election or the geopolitical whims of great powers to improve our outlook is a dangerous illusion, as has been repeatedly proven throughout Cuban history.

“It is clear that [Cuba’s] potential cannot be unleashed by public entities alone and the perverse incentives they create. A market-driven coordination system is crucial in order to reduce distortions in our productive sectors and improve the measurement of economic activity.”

Full use of the talent and energy of the Cuban labor force cannot be achieved by the country’s current state firms, at least not most of them. It is clear that this potential cannot be unleashed by public entities alone and the perverse incentives they create. A market-driven coordination system is crucial in order to reduce distortions in our productive sectors and improve the measurement of economic activity. It is also necessary for improving the conditions of Cuban enterprises that compete in foreign markets. A functional market must not be seen as a synonym for an unregulated or frenetic one.

Referring to its relations with the United States, Cuba must recognize the position of the former in the international order. Even though the Cuban economic dimension is not relevant to the United States a whole, this does not have to be the case to specific states or industries. That is a kind of approach which must be boosted in the near future. Any economic exchange based on information networks contribute to the cutting of costs generated by trade with more distant markets. Instead of pondering solely on when the embargo will end, the most important question for the leaders of the Island should be: what are we doing to prepare ourselves to use this hypothetical favorable situation to our advantage?

Dr. Ricardo Torres is a professor of economics with the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy at the University of Havana.

References

Bolt, J., Inglaar, R., de Jong, H., & van Zanden, J. (2018). Rebasing ‘Maddison’: new income comparisons and the shape of long-run economic development. Groningen: Madison Project Database version 2018. Obtenido de www.ggdc.net/maddison

Gorey, R., & Dobat, D. (1996). Managing in the knowledge era. The systems thinker, 7(8), 1-5.

Jorgenson, D. (2018). Production and Welfare: Progress in Economic Measurement. Journal of Economic Literature, 56(3), 867-919.

Kornai, J. (2014). The soft budget constraint. Acta Oeconomica, 64(S1), 25-79. doi:10.1556/AOecon.64.2014.S1.2

Mearsheimer, J. (2019). Bound to Fail. The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order. International Security, 43(4), 7-50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00342

BACK TO NUEVOS ESPACIOS