Glenda Boza Ibarra

Private Sector in Cuba: An Opportunity to Empower Women

Economic independence, increased income, the ability to select the right or desired job, and teamwork with colleagues or family, constitute the primary motivations for Cubans who have embraced self-employment (cuentapropismo), whether as contract workers or business owners.

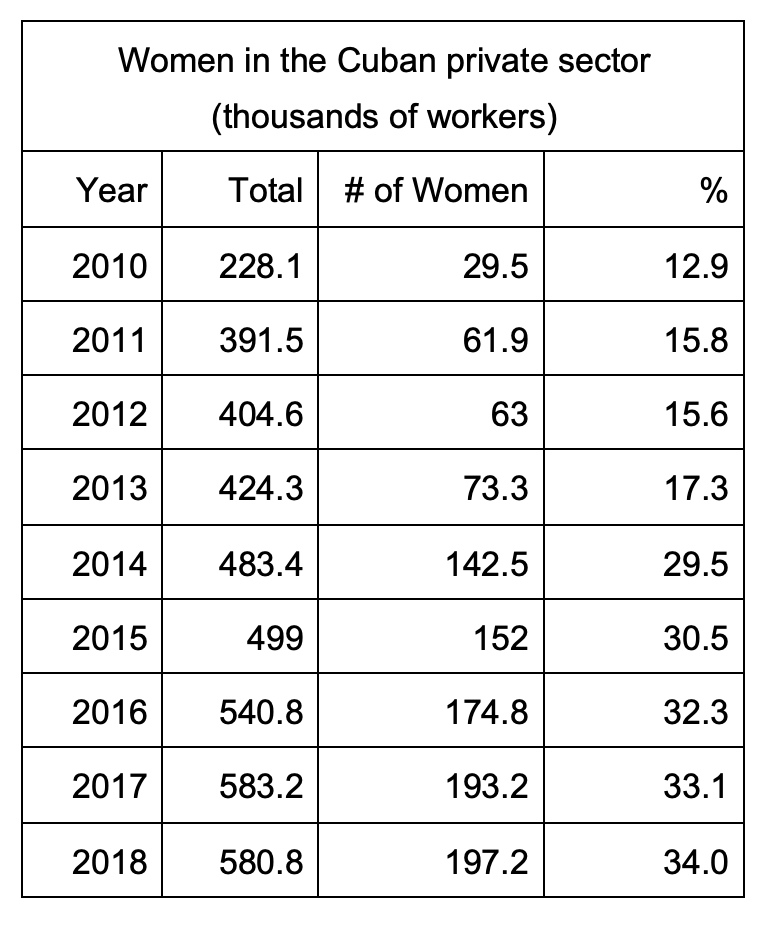

However, Cuban women represent only 33.9% of total cuentapropistas. Although their proportion within the total of self-employed workers increases every year, that number has never risen above 35%.

With so little representation, the contributions of Cuban women in the private sector may seem insignificant; however, female entrepreneurs on the Island have shown not only that they can be financially successful, but also contribute to breaking gender biases and empowering women. But what causes still hold Cuban women back from joining the ranks of the non-state labor force? How have successful business owners overcome these obstacles? This article explores some problems women face in the complex context of the Cuban private sector and highlights several successful examples of Cuban women who have managed to overcome these challenges, while revealing possible paths for other female-run enterprises.

Attention to Labor Matters

There are several motivations for women to pursue entrepreneurship in Cuba, most common among them increasing personal income and leaving the ranks of the unemployed.

However, these reasons are not sufficient to commit to entrepreneurship. Many Cubans do not dare to dive into the private sector due to job insecurity and the absence of contracts and vacations – which protect state sector employees.

Often in the Cuba non-state ecosystem working arrangements are agreed upon between employers and employees through verbal agreements in which fixed minimum wages are not determined, but hourly payments are.

Although the right to wages and personal time off are earned spaces for Cuban state workers – as established in the country’s Labor Code – these protections are not always respected and ensured in the non-state sector. In the case of contract workers, the right not to lose your job after obtaining maternity leave, although remunerated and established by law, is one of the most commonly defied outside of state labor.

Add another situation: faced with the demand for employment in the private sector, many women may not be willing to demand their rights to keep a coveted job and for which there is intense competition.

Although these situations –born of job insecurity and a regulatory framework that establishes difficult-to-enforce rules– have been recognized by organizations and ministries that should encourage, train and ensure compliance with labor rights, such as the Ministry of Labor and Social Security and the Federation of Cuban Women, respect for these legal guarantees is applied in a discretionary manner and according to the understanding and circumstances of each business owner.

Some self-employed women assert that when their employers are also women, there is a better understanding and respect for these guarantees, perhaps due to a matter of empathy and solidarity.

However, it should be made clear that there are other state policies that protect self-employed mothers, such as the access to early childcare and part-time schools. In addition, the compulsory affiliation of cuentapropistas to the Social Security system offers protection against maternity, old age, temporary or permanent total disability, and deaths in the family.

Beyond Social Expectations

In Cuba, the majority of women who work in self-employment (70%) fill positions traditionally associated with women: manicurist, seamstress, childcare and elderly care, hairdresser, makeup artist, domestic staff, costume rental, washing machine, reviewer, decorator or music teacher.

Due to strong patriarchal influence in our society, stereotypes persist as to what trades are “destined” for women, and many do not consider jobs that are not traditionally associated with the female sphere. In this way they not only limit their individual potentials, but also their opportunities.

However, several examples show that they can also be successful in “masculine” tasks.

Led by women, Veló Cuba – a bicycle repair and rental workshop in Havana – and Constructora Gotera – dedicated to the repair and restoration of real estate – are case studies of how some Cuban women have found paths to empowerment, success, and job creation in “unconventional” trades.

Since 2017, Veló Cuba has achieved an alliance with the Office of the Historian of the City of Havana to work on the Habici project, a public mobility initiative that installed the first public bicycle system in the country’s capital.

Likewise, Constructora Gotera extends its work through various provinces and has carried out important works such as the restoration of the domes and towers of the Hotel Nacional.

Advancing the feminization of labor activities is not simply a “moral” achievement, it can also represent personal and economic growth. Quality work has guaranteed contractual relationships with the State that not only allow for higher incomes, but also greater access to resources and more guarantees of job offers extended over time.

Such is the case of Ciclo Ecopapel – a venture that produces eco-friendly paper (without chemicals or artificial binders) – and launched by offering services to the Antonio Núñez Jiménez Foundation, its first client. Its founder and director chose the venture not only to increase her income, but also as a way to spend more time with her daughter.

Women’s Networks

The positive impact of the private sector is reflected in the increase in the number of women active in this space. Although most of them are not business owners, but rather act as contract workers, a discreet but constant growth is evident: both among women in the sector and in their proportion to men. (Table 1)

However, dedicating on average 14 hours a week more than men to unpaid domestic tasks such as caregiving and homemaking is a factor that prevents many Cuban women from pursuing entrepreneurship.

The instability of supply in the retail network poses another obstacle. There is only one wholesale vendor in Cuba. Add to that legal insecurity and bureaucracy, the cost of imported goods, and the risk of informal markets and payments of customs taxes.

In several cases, due to the absence of support programs and actions that encourage female entrepreneurship, many women end up almost “forced” to opt for contracted work and existing subordination schemes in Cuba.

However, many successful female-led ventures have shown that it is possible to overcome these obstacles. appealing to creativity, women’s networks and the selection of work activities with market demand.

Given the scarcity of products and a wholesale market, several business owners have had to get creative and reinvent themselves, and that is a virtue that Cuban women, almost always heads of households, seem to have in their genes.

Appealing to that creativity, the home design shop La Bombilla, and craft studio Rústica Cuba, use recycled materials and offers unconventional products with a secure market.

La Penúltima Casa, for example, is a digital communication initiative that provides solutions, training and advice tailored to the Cuban reality and mainly focused on the management of social networks for central organizations.

Penúltima Casa founder Katia Sánchez Martínez noticed a lack of information, knowledge and good practices in Cuban organizational, institutional and business communications, and recognized a market opportunity for her digital marketing services.

Some self-employed women workers have also chosen to create entrepreneurial networks, not only to share experiences but also to integrate services. The operation of these networks is clearly evident among home renters, who not only offer lodging services, but also associated services such as private transportation, recreation and food, throughout the country.

Some receive commission, but, in many cases, the real gains come from word-of-mouth recommendations in other provinces. For many hosts the measure of success is having a repeat clientele, which they achieve with quality service and as comprehensive as possible.

Furthermore, women have a greater tendency to associate, thereby sharing both opportunities and risks.

Saily González, owner of the Amarillo B&B hostel in Santa Clara, founded the FullGao project with the goal of sharing her knowledge in positioning content on online booking platforms.

The collaborative network not only offers advice to other tenants but also provides photography, interior design and other services. Many of the entrepreneurs who joined FullGao claim that their clients have increased since the association.

Similarly, Beyond Roots decided to link businesses that promote Afro culture in Cuba. Founder Adriana Heredia integrated several projects into a comprehensive service — gastronomy, sightseeing tours, recreation, shopping — all centered on the promotion of afro-cubanismo.

The shortage of products for black women has not stopped being an obstacle for Heredia, but Beyond Roots’ success is based on connections and networks among entrepreneurs whose businesses were not well-known.

These, like other projects, not only influenced the individual and professional growth of its owners, but also that of other women and of the community itself.

Some Proposals

Although the research into the role of women in the Cuban private sector remains lacking, anecdotal evidence suggests that women have not yet adopted traditionally “male” leadership practices, assuming instead more supportive and empathetic ways of collective work and shown greater personal commitment to their workers.

Taking into account the possible economic, family and emotional advantages of incorporating women into self-employment, there are several factors that may widen the path for women.

Greater access to advisory services on labor rights, marketing, business administration, accounting issues, legal frameworks and basic knowledge to start a business are necessary and of urgent need for Cuban self-employed women. Proyecto Cuba Emprende offers workshops and training to the private sector in Havana, Cienfuegos, and Camagüey. Yet other provinces lack these or similar courses. According to Cuba Emprende’s own data, women are the most interested in these workshops, perhaps because they are not afraid to acknowledge their lack of knowledge and need for support.

Increasing state policies and options for credit and financing – whether national or international – to develop business models that generate female employment and extend to the community, would favor start-up generation by women eager to become entrepreneurs, but lacking the financial resources to do so.

Expanding public-private alliances, mainly with successful businesses led by women, can contribute to breaking gender stereotypes in society. It also urges government agencies to promote measures that recognize the value of women’s unpaid work as labor.

Creating effective mechanisms to monitor compliance with labor rights and legal guarantees and protections is another urgent need in Cuba.

Entrepreneurship always carries risks. Beyond the challenges described, the growing integration of women into the non-state sector has contributed to a progressive decrease in the unemployment rate among Cuban women: from 3.5% in 2011 to 1.8% in 2018. Cuban women bet on self-employment and have shown that it is possible to start a successful business in their country. Much potential remains untapped, but it is essential to understand that in the case of women, entrepreneurship works as a network: an entrepreneurial and empowered woman almost always helps empower other women. They all win.

Bibliography

Díaz-Fernández, Ileana; Echevarría-León, Dayma. Entrepreneurship in Cuba: an analysis of women’s participation In: Entramado. July December. 2016 vol. 12, no. 2 P. 54-67, http://dx.doi.org/10.18041/entramado.2016v12n2.24239.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. http://www.gemconsortium.org/country-profile/109.

National Statistics and Information Office (ONEI-Cuba): Statistical Yearbook of Cuba 2018. Havana, 2019.

National Statistics and Information Office (ONEI-Cuba): Demographic Yearbook of Cuba 2019. Havana, 2020.

National Assembly of People’s Power, Law 116 of 2013, New Labor Code.

BACK TO NUEVOS ESPACIOS