María Lucía Expósito

Cubans in Crowdfunding: The Era of Collective Financing

The last six years have seen a rise in Cuban initiatives on online platforms. The phenomenon has gained momentum after the expansion of the Internet’s infrastructure with the use of mobile data networks. In the midst of this context, several projects have been developed domestically through the use of crowdfunding, which has become a gateway for production and financing.

Its success, which is based on internet donations, has been how many independent initiatives in Cuba have been able to materialize, or at least develop part of the logistics they need to carry out their projects. Musicians, illustrators, theater groups, film directors, and social causes have expanded their financing models to this online alternative.

Crowdfunding goes beyond asking for monetary support. It is also a way to raise funds online from person to person. The most successful projects in raising money are those that describe what each donor will receive in exchange for their contributions. Platforms like GoFundMe, Kickstarter, and Indiegogo allow you to create campaigns through their websites. Some, in addition to raising money, create a community around the campaign. Others allow you to collect what has been raised even if it hasn’t reached the total goal.

Part of the success in raising the necessary funding will depend on the campaign goal set by the organizer. It could be focused on helping specific people, for example, a family that lost all of their belongings in a fire. It could also be established as a collaborative effort with groups of people, like a cause, such as helping those who have been impacted by a natural disaster in a particular area. Sometimes, the campaigns have commercial purposes, such as raising money for a business. The donations gain momentum and feedback through posts on social media and on the crowdfunding websites.

There are many crowdfunding platforms, each of them with their own rules that range from how much money the site will retain, such as fees, to how and when the money will be delivered to the campaign organizer, and who will receive the money after reaching the goal. In Cuba, the most recognized platform to facilitate money contributions is Verkami.

Verkami is a platform dedicated to crowdfunding. It was founded in 2010 by the private initiative of a father and his two sons. Mainly aimed at creators, artists, designers, and groups, Verkami offers specialized and personalized assistance. It is a cultural and social platform, although the range of projects published on the site is becoming more and more extensive. “Cinema and music make up a large number of the projects; publishing projects are the most successful,” reveals the website.

In Cuba, Jorgito Kamankola was the first musician to finance an album through crowdfunding. His was the first CD to be completely financed through this channel, though it was later banned. But he managed to raise 3,000 euros in 40 days on Verkami, which facilitates payments because it is based in Spain. “We asked for 3,000 euros and we got it,” he says. “The money went to a foreign account and then the rewards to the patrons.”

Among the gifts for those who had collaborated were a record with each name in the acknowledgments, a dedicated video and so on, “so that people would be interested in donating what they could and receive something in return that showed our gratitude,” he says. Jorgito publicly assured that it was cheaper than if he had done it in Cuba. Internet access was more complicated in those days.

In 2016, the video game Savior, the first independent or indie prototype produced in this way in the country, was able to collect $12,975. Launched by the young Josuhé H. Pagliery and Johann Armenteros on the Indiegogo website, their campaign was supported by Innovadores Foundation, an American foundation which gave it visibility in the U.S. That same year, the filmmaker Yimit Ramírez launched the campaign for the independent film I Want to Make a Movie (QHUP). To encourage stakeholders to collaborate, they designed various types of participation. For a minimal contribution, one could receive a caricature made by the director, the promise that the collaborator’s name would appear as a patron in the film credits, or the obtain a code to watch the film’s premiere in high definition.

“The U.S. embargo towards Cuba exists, and these examples are proof,” explains the Cuban communicator, activist, and feminist Marta Maria Ramirez, who was in charge of managing projects’ social networks since most platforms disapprove of proposals where Cuba is the final destination for funds. Before QHUP, projects such as Venecia, by Kike Álvarez, Dark Eyes, by Jessica Rodríguez, Agosto, by Armando Capó, and El secadero, by José Luis Aparicio Ferrera, were successfully carried out thanks to this method.

Between 2019 and 2021, many Cuban art collectives also joined the crowdfunding experience. Among the most recent was for a staging of the Shakespearean play Richard II, by the Perséfone Teatro group, which was able to raise 3,000 euros in the first days of the year. Another is the Casa Palanca project, which sought to raise 25,000 euros to establish a physical space that would serve as refuge for independent women journalists in Cuba.

Adonis Milan is an independent Cuban theater director, now separated from institutional protection. Through international aid and his own discovery of crowdfunding, he managed to pay for the production to bring Richard II to the Cuban stage. During the campaign to collect funds, Perséfone’s social media was dedicated to promoting the donation link, in addition to the cast that makes up the show. Milan managed to raise part of the production costs thanks to collaborative spaces like this and according to the artist, he will continue using this avenue to support other theatrical plans.

For its part, Casa Palanca defined in its guidelines that it was not just a campaign to bring visibility to the ordeals of Cuban independent journalists. It was focused on collective funding, where 100% of the resources were going to be used to buy a physical space in Havana to meet, work, care for, and welcome women journalists who need it, including their children. Each day they shared one-minute videos on their social media where each participant spoke about her experience as a woman and a journalist. Along with a visual campaign calendar, there were updates to the community of followers and allies about the contributions and their patrons.

For Marta María Ramírez, spokesperson and coordinator of the Palanca networks, this was the first social cause she helped organize outside of the commercial sphere and the one with which she most identifies. This is because of the need to build a refuge and safe place for vulnerable communicators, activists, and independent reporters within the country.

The perspectives on crowdfunding in Cuban spaces have also transcended to cryptocurrencies. The development team of the AFondo team promotes a value scheme: “crowdfunding + cryptocurrencies = cryptocrowdfunding,” and is designed to promote startups in Cuba.

AFondo, an idea of Abel Bermúdez Muñoz, offers an efficient financial management model for the average Cuban since traditional payment gateways are inaccessible. Hence, it is an administrative decision to use only cryptocurrencies as a financial asset, in addition to the fact that the cryptocurrency they use, the USDT-TRC20, has a 0% transfer fee.

The business scheme is quite similar to that of traditional crowdfunding platforms. Its value lies in the fact that the sponsors make contributions through cryptocurrencies. The contributions are received by the platform, and when they reach the established figure, a priori, they are transferred to the entrepreneur with a 9.5% fee, a commission charged by the company for management. If the fundraising goal is not reached within a period of 30 calendar days, the campaign ends and 100% of the money is returned to the contributors without additional charges.

Regarding this point, a news item from December 2021 reveals that the crowdfunding site Kickstarter, seeing the changes in trends on the networks, has decided to embrace cryptocurrencies. The portal will create a new blockchain-based[1] crowdfunding platform to move to once it is ready. It will take the concept to a new level that it will allow any user to use the infrastructure to set up their own crowdfunding portal.

Although all signs suggest the immersion of Cubans in crowdfunding will continue to grow, along with digital culture and art in online spaces, there are still roadblocks reported by project organizers such as slow connections and problems with accessing the websites in order to manage their data. Many have had to install virtual private networks or VPNs to complete forms and keep campaigns active. Meanwhile, new projects join those that have already established a trajectory. Advice is shared from project to project. Many repeat the experience. Collective financing knew how to gain ground as an alternative to support entrepreneurship in the Cuban 21st century.

María Lucía Expósito is a journalist and poet. She writes about technology, film, literature, and other good herbs. She is a photographer without manuals. She investigates issues about social and environmental journalism. She lives in Havana.

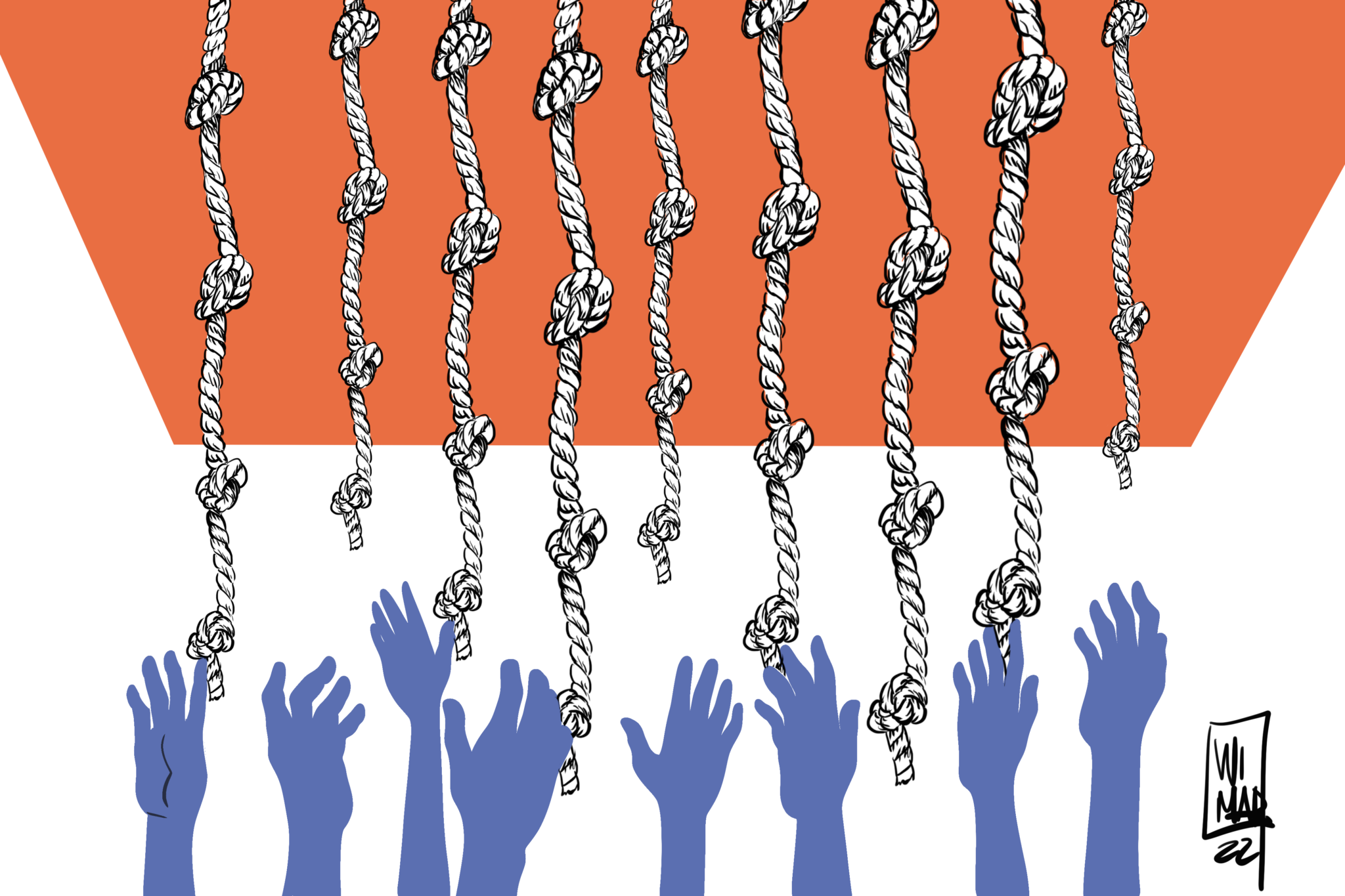

Illustration by Wimar Verdecia Fuentes. Find him on twitter @FuentesWimar

[1] Set of technologies that allow keeping a secure, decentralized, synchronized, and distributed record of digital operations, without the need for third-party intervention.

BACK TO NUEVOS ESPACIOS