Oscar Fernández Estrada

The Time for SMEs in Cuba?

The prolonged emergence of Cuba’s private sector is making headlines once again. On August 20th, 2021, after being postponed several times, long-awaited legal regulations were issued that recognize the private sector as an organic part of the Cuban economic system.[1] Among the most relevant parts of these regulations is the possibility to create small private companies that are recognized as their own legal entity. These entities have the authorization to exercise independently from the State in a wide variety of economic activities.

Reform, Counter-Reform, and Reform.

By the end of 2010, with Raúl Castro at the head of the government and the Party, there was an economic reform being promoted—officially known as the “Actualization”—which proposed, at least in principle, incorporating more market elements in the allocation of resources in the economy, a greater decentralization of state companies, more prerogatives for the territories, as well as an increase in the participation of private property, euphemistically called “on-state,” in the economy.

When new laws began regulating self-employment in October 2010, private parties were openly authorized to hire a workforce. Therefore, the government tacitly recognized the existence of privately owned businesses, at least on the scale of microenterprise. This change became one of the most momentous conceptual transformations in the last 50 years. Under these conditions, self-employment grew to more than 70% between 2010 and 2011. It continued to grow until the start of the pandemic, although not without setbacks and counter-reforms.

In 2013, the government issued Decree Law 315 in which it sought to give “order” to the private sector by imposing restrictions that limited the scope in the description of each authorized license activity. In that moment, activities that had authorization to operate were shut down and some people lost investments. Such was the case with 3D cinemas.

Then, at the beginning of 2017, the government caused tension with the private transportation sector when it chose to establish maximum prices for sections of service. The transportation companies responded with a general strike in Havana, and some protested in other provinces.[2] In August 2017, under the argument that the new rules would be studied in order to “perfect” self-employment, the government interrupted granting licenses indefinitely for some of the most prosperous activities, such as renting apartments, and cafeterias and restaurants. It was not until almost a year later the new regulations were issued[3]—signed by outgoing president Raúl Castro—this time with new restrictions. One of the most impactful laws limited each citizen to carry out only one license activity, which affected all the businesses that had been developed from the synergistic combination of several licenses. It was back to business in its simplest form.[4]

All of this happened in a contradictory context. On the one hand, normalizing relations with the United States had produced a favorable economic bonanza with the proliferation of American travel, as well as a promising future for state companies through some joint contracts.[5] On the other hand, Obama’s visit and declarations of support for the private sector as an agent of political change in Cuba fueled distrust. It symbolically empowered conservative sectors within the Cuban government, which halted the march toward transformations.

Paradoxically, the 7th Congress of the PCC had taken place in 2016, which continued the path of the reforms initiated in 2011 by deepening the expansion of the private sector and the market and decentralizing the state sector. This was done by approving the so-called Conceptualization of the Economic and Social Cuban Socialist Development Model that would be, in theory, the governing document for economic policy the following five years.

During his reading of the Central Report for the Seventh CCP Congress, Raúl Castro raised concern for the need of legal recognition of SMEs. However, from then on, events or circumstances within the government—which until today remained unexplained to the public—operated in the opposite direction to what was agreed upon in the Congresses.

Finally, due to its notorious irrationality, in addition to popular reactions that were spurred by the 2018 restrictions, the reforms were significantly reversed just before they came into force in December of the same year, in one of the first decisions adopted by Miguel Díaz-Canel in his new role as president. Díaz-Canel introduced new corrections in 2019 that demonstrated his determination to push ahead with the Actualization.

Crisis as Catalyst

During the last two years, the Island has gone through a severe economic crisis as a result of a sudden combination of three main factors. The internal development model had been exhausted, in addition to its demonstrated inability to generate minimum changes to reduce the mono-dependencies and structural deformations of the Cuban economy. This was evidenced in the meager growth rates during the years prior to the pandemic.[6]

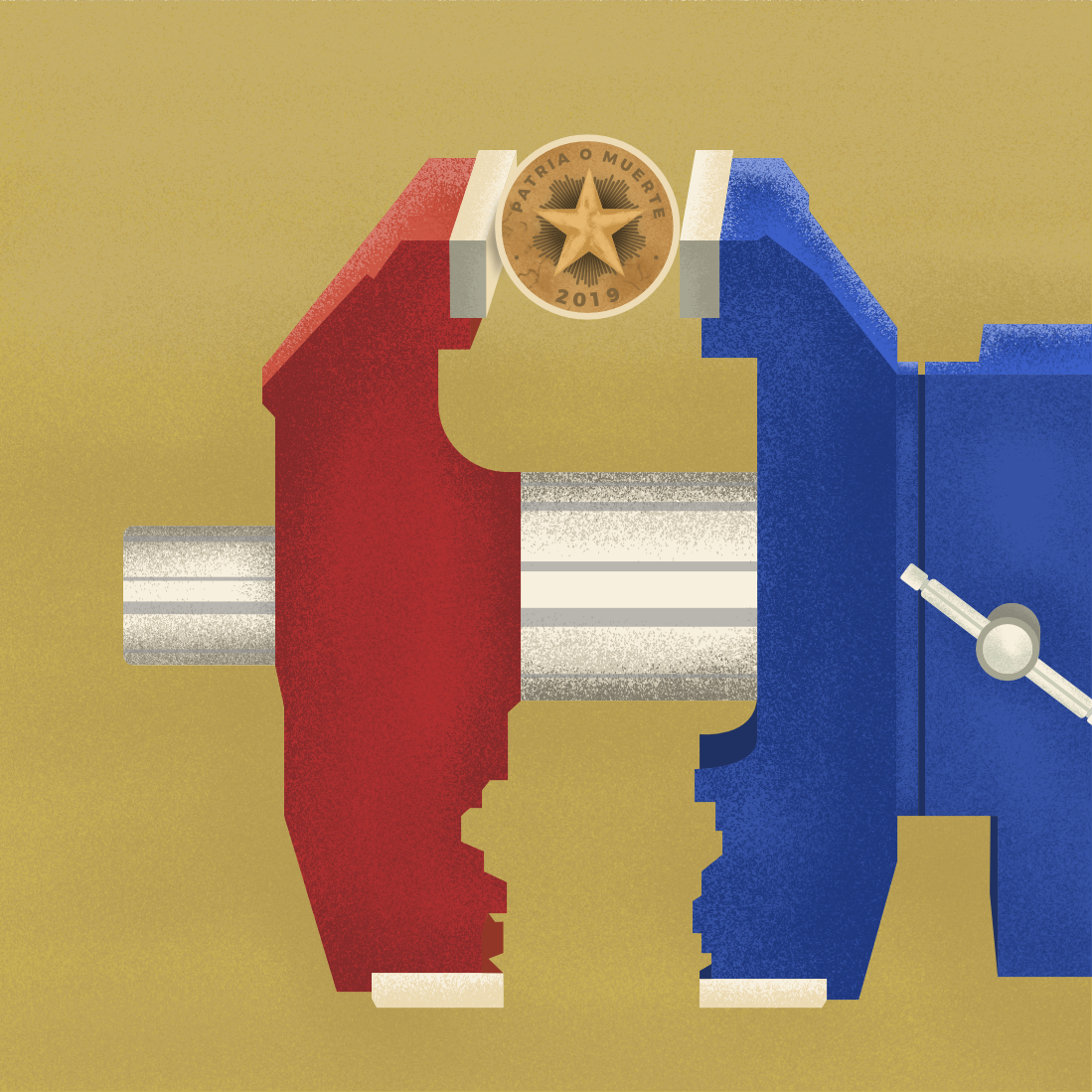

The severity of economic sanctions imposed for decades by the U.S. government achieved maximum chokehold levels during the last months of the Trump administration and has persisted without significant change during the first year of Biden’s presidency.

Perhaps the most relevant factor in the short term was the sudden, forceful, and sustained external shock generated by COVID-19 that evaporated tourism and income from exports for the national economy.

The crisis, which is also a result of the severe inconsistencies, slowness, and stubbornness in economic policy decisions such as the monetary unification process,[7] and which climaxed in the recent July 11th protests, has forced authorities to act. This has probably modified somewhat the distribution of forces within the government, slightly and temporarily tilting the balance towards those sectors that long advocated reform.

It is important to highlight that this opening, despite being under a high-ranking legal norm such as a Decree-Law, is built under the protection of a fragile, incomplete, and ultimately reversible consensus, which is why it was created with unnecessary restrictions, useful only to satisfy certain sectoral interests. Such is the case on prohibiting lawyers, architects, accountants, tourist agencies, among other professionals, from entrepreneurial endeavors. Other restrictions, such as the prohibition against establishing private SMEs with non-resident partners, or forbidding that a partner is part of more than one company, or the obligation that a company must transform when it exceeds 100 members, could be interpreted as a concession to more conservative thinking, but they also reflect the counterweights manifested in the debate at a social level.

Despite it all, the adopted measures should not be classified as superficial or cosmetic. The bet is clearly strategic. The scope of what is authorized now is very broad, and evidently it breaks with some of the stagnant approaches of the previous economic model. From the government’s point of view, the private sector can no longer be seen as a mere adjustment variable that can be interrupted or encouraged according to prevailing winds. It is now an increasingly present and stable actor with full economic and social rights and responsibilities.

Challenges of this New Stage

The new era of non-state economic activity in Cuba will unfold in a highly complex context. And although there are some noteworthy opportunities, it will have to overcome enormous obstacles to consolidate itself. The first and most complex challenge is the uncertainty associated with the macroeconomic environment, especially in monetary variables. The devaluation of the Cuban peso in January 2021, with the aim of correcting the exchange rate distortions that dragged on for decades, coupled with an incomplete reform of wages and prices, have plunged the country into a kind of inflationary chaos.[8] A macroeconomic readjustment of such magnitude is always the source of very significant uncertainties. And in this sense, for example, feasibility studies to support investment decisions will be more difficult.

The current state of the sanctions policy imposed by the U.S. government presents the second largest obstacle. Biden’s electoral promise to return to the rapprochement promoted by Obama generated hope among Cuban entrepreneurs, but remains unfulfilled. Relaxing restrictions on financial flows and promoting travel for Americans to the Island could mobilize financing and stimulate aggregate demand, which could favorably impact domestic production.

Profuse supply gaps undoubtedly complicate the development of stable supply chains, in addition to the acquisition of inputs and components. In many cases, there are no options other than to import, which is only possible when a business has enough demand in MLC for its production, given the dearth until now of a legal exchange market where private companies (not even state-owned companies) can acquire MLC with their assets in pesos.

However, at the same time, the supply crisis itself becomes a magnificent opportunity. Cuba is characterized by virtually virgin markets, almost hidden from transnational monopolies, with few suppliers, limited variety of goods (many of relatively low quality), and unstable offers. Therefore, it is very easy to find a viable business idea, even those already proven in other latitudes.

Additionally, transformations to the management model of state-owned companies are also underway—with lower public profiles and thus greater autonomy.[9] This will facilitate horizontal economic relations between all actors. The private sector would benefit from direct access to certain supplies reserved until now for state clients, as well as purchasing power for their production, while the state sector could find flexible, fast, and relatively inexpensive solutions to problems that usually emerge upstream through central planning.

On the other hand, an important space for the development of private enterprises lies in Local Development Project alliances (or public-private partnerships) with municipal governments. For some time now, the central government has been decentralizing certain functions to local levels. This transfers the responsibility for solving many of their own problems to them. Although it depends a lot on the leadership and daring of public officials, and there is a large bureaucratic trail to overcome in these types of projects, there are important opportunities along this path.

Final Comments

The new rules offer a relatively adequate margin for the small-scale private sector to take its first steps. However, they have yet to create conditions in other aspects, which are also key, for ventures to succeed, and particularly for their integration within the economic system.

First, there need to be long-term guarantees for the stability of the regulatory framework. This is the only way that emerging ventures will bet on productive projects of greater importance—those that generally require more time to mature and involve a greater investment—instead of tackling entrepreneurial activities with a rentier focus. The authorities haven’t exactly won the confidence of entrepreneurs in recent years. The economic model has experienced brutal ups and downs when conceiving the private and cooperative sector, as well as the role of the market. The government must find a way to guarantee that this regulatory framework being established today will not backtrack in a couple of years. The current governing norm of Decree-Laws constitutes an important signal, but it would be much better if laws were ratified by the National Assembly.

On the other hand, it is essential to demonstrate simplicity and speed in approval procedures and to minimize space for administrative discretion. The authorities appear to have invested efforts in this regard. As has been widely disclosed by the Ministry of the Economy—the institution in charge of leading the process—any project that requests to operate in unrestricted activities that meets the requirements established by law must be approved automatically. This minimizes space for discretion. In order to manage the presumed avalanche of applications since the regulations came into force, they have decided to launch gradual calls ordered by activities, starting with the priorities of economic policy.

But the most critical point, in my opinion, lies in the scarcity of financing options. The authorities have mentioned the possibility of having a fund in MLC to promote private activities with export potential. However, that is the weakest point in the entire system. State commercial banking, accustomed to half a century of no competition and heir to a model that has underestimated the role of money in the economy, has shown very few skills in adapting to the needs of this growing sector. It will remain out of the private market, as it has since 2011. Make no mistake: many ventures will emerge. Most of them will find ways to finance themselves. The regulations recognize the right of SMEs to accept financing from any legal source. External financial institutions, foreign funds investments, natural persons, etc., have quickly inquired about possible ways to participate. Entrepreneurs, for their part, need training and education to achieve fair negotiations with potential lenders.

One pending issue that has not yet been considered by the authorities is eliminating the obligation to have a state-owned company intermediate for foreign trade operations. Current regulations show an essentially rentier environment, not only because it guarantees a captive market designed for intermediaries, but also because it requires MLC payments for these services, which are not always attributable to foreign exchange expenses corresponding to the process itself. In addition, the conglomerate of companies authorized for foreign trade is also limited, and with “distributed” areas of specialization. This only perpetuates the inefficient monopolistic structures that have traditionally supplied the state sector. However, the further that relationships between state-owned companies and private enterprises advance, the more opportunities will arise to satisfy certain demands for mutual inputs. Facilitating legal avenues to access MLC, as soon as macroeconomic conditions allow it, is another of the essential issues for the replenishment and survival of these ventures.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the creation of the so-called National Council of Economic Actors, which is established in Article 10 of DL-46, and which would apparently function as a kind of policy coordination institute for the promotion and development of non-state actors. This is unprecedented in the Cuban economy since 1959.

Oscar Fernández Estrada is an economist and consultant. He has a doctorate in economics from the University of Havana, 2008 and has co-author several books on Cuban economics. He has lectured at universities in various countries, such as the United States, South Africa, Vietnam, Venezuela, and Jamaica.

Illustration by Maikel Martínez Pupo. You can find him @MaikelStudio @maikelmartinezpupo.

[1] Ordinary Official Gazette No. 94. August 19, 2021.

[2] This phenomenon was unleashed when the Cuban authorities, as a result of external tensions aggravated by the persecution of the US government, are forced to apply a cut to the fuel that they centrally assigned to state companies. The private transportation sector was affected since most of the fuel they consume comes from diversions by these state-owned companies and not from purchases in the service center network. So, they raised their prices and their interdependence with the illegal fuel market was made transparent. The government reacted by trying to force the old price levels and the carriers responded by interrupting the service.

[3] Extraordinary Official Gazette number 35, July 2018.

[4] To illustrate with a simple example: a car scrubber offered owners a free refreshing drink while they waited for their car. Under the new rule, the scrubber was prohibited from offering this supplementary service, even if it was free.

[5] Such is the case of the Cuban hotel Four Points by Sheraton, which was handed over to the Merriot hotel company. The Trump administration just terminated that contract, forcing Merriot to terminate its activities in Cuba.

[6] Between 2016-2019, GDP grew at an average rate of 1.08% per year. https://datos.bancomundial.org/

[7] The Monetary Regulation process, which was originally planned to solve the problem of the double circulation of currencies and the duality of exchange rates, saw its objectives contaminated with the previous appearance of the offers in Freely Convertible Currency. Its implementation was reduced to the elimination of the CUC, a devaluation of the Cuban peso (CUP) of 2300%, together with a regulated increase in prices and state wages. All of this, without having previously created the conditions for the state-owned companies to have the necessary autonomy to allow them to make their adjustment, and without authorizing a private supply that could respond to the unsatisfied demand for goods and services, the result is chaos in the free-form pricing system resulting from a loss of benchmarks, which finds more and more foothold in the price of the dollar on the informal market.

[8] For most free training prices.

[9] Official Gazette No 80 Extraordinary 2021.

BACK TO NUEVOS ESPACIOS