Laura Seco Pacheco

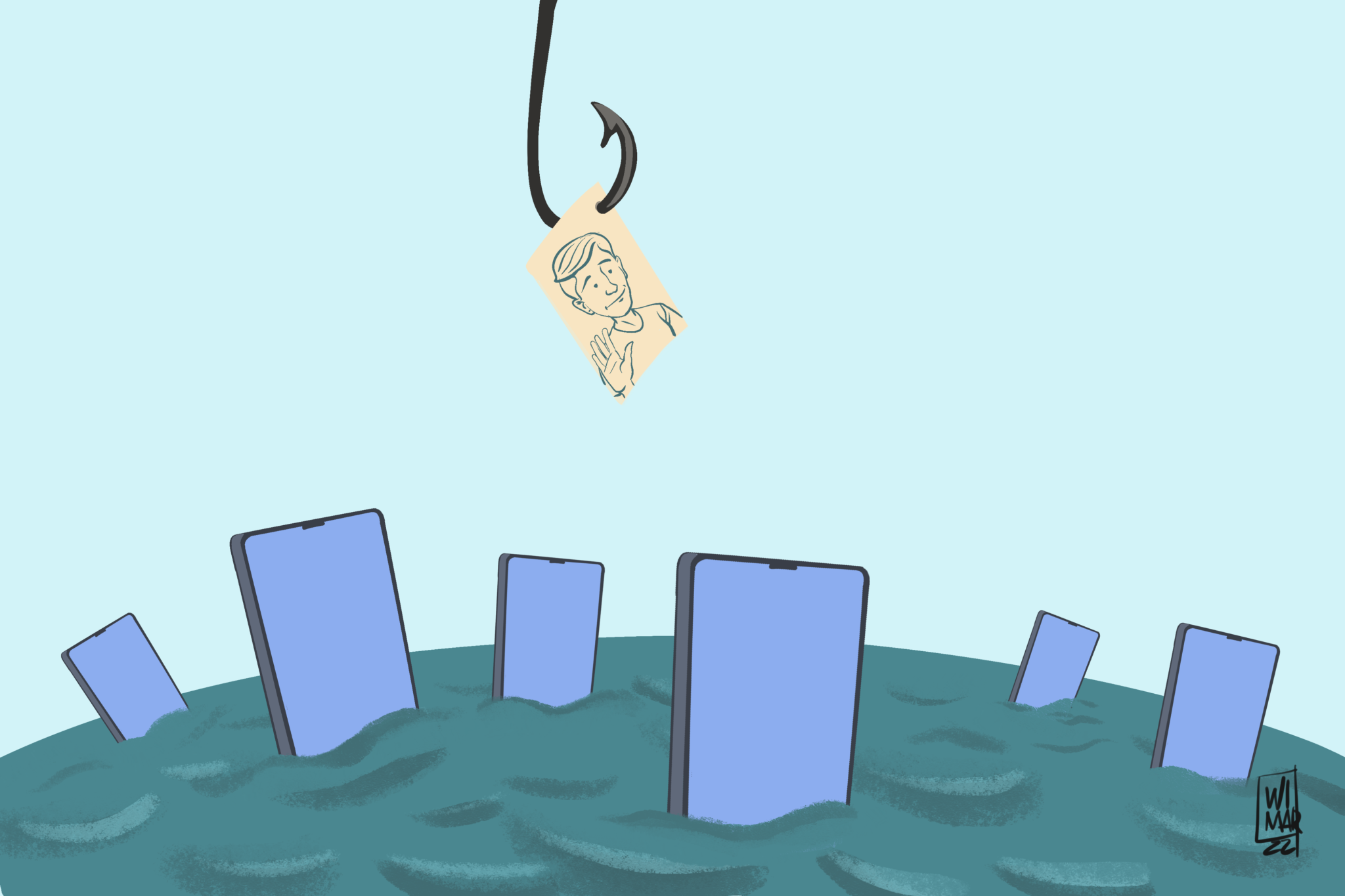

“Is That You in the Video?” Phishing and Data Protection in Cuba

“No, you do not appear in the video. Relax. Don’t take the bait, and don’t open the link. Close the chat, change your password, and report the problem.

For weeks, Cuban Facebook users have denounced mysterious messages arriving through Messenger. “Is that you in the video?”, they read, followed by a few emojis showing amazement, or anguish (sometimes they vary), and a link.

To the credulous/curious who click on the link, it sends them to a page with an identical design to that of Facebook, with two fields in which they ask to enter the username and password of said network to log on. On a mobile phone, it could go unnoticed, but if you perform the procedure on the computer, you can verify that the URL that appears in the address bar does not match or bear any relation to Facebook.

It is a hacking strategy to obtain new users, get hold of their personal information and, incidentally, trick your contacts. So far it has not been possible to determine the purpose of the scam, but theories abound on the web. Who is behind it remains unknown.

This phenomenon is known as phishing. It consists of gaining a user’s trust by passing on a message that someone they know would send. Of course, this isn’t new, much less on Facebook, but it has been mutating and adapting to different online spaces depending on the objectives of the cybercriminals who execute it.

Cubans, despite being late to tech availability and access, have not been immune to it, nor from other schemes that violate their privacy and can lead to large scams. To make matters worse, they do not have legislation that protects them against this type of situation in the virtual world. At least, until now.

Phishing: An Old Strategy, Renewed

Microsoft’s website defines phishing as “an attack that attempts to steal your money or identity by having you divulge personal information (such as credit card numbers, banking information, or passwords) on websites that pretend to be legitimate sites.”

To achieve this, hackers pose as reputable companies, friends, or acquaintances through a fake message that contains a link to a phishing website. They not only use direct messages from Facebook or WhatsApp, but also emails, video game messaging, and even phone calls.

The term has its origin in the Anglo-Saxon word to fish (fishing). The digraph “ph” comes from some of the first hackers who in the 70’s were known as “phreaks” (phone + freaks). In an emerging, interconnected world, they carried out small scams to make long distance calls.

The term became popular in the 1990s. The first great victim was America Online (AOL), the number one provider of Internet access at the time, with millions of daily connections. The hackers arranged for users to share their AOL accounts and passwords, which they later used for spamming and similar maneuvers.

The banking system is one of the main targets of phishing, mainly through credit cards and personal accounts, with losses amounting to millions of dollars for victims.

Phishing does not require great technical knowledge, nor the use of large programming codes. The danger lies in its simplicity. Through hacking tools, such as manipulation or identity theft, the same victim is the one who reveals confidential data.

This “market” has advanced so much that there are phishing campaigns organized by professionals. These operations can even be outsourced, or web pages “rented” as phishing bait. These websites are often exact replicas of the pages being spoofed. In addition, the messages include a whole series of mechanisms to avoid spam filters.

The ease with which it can be committed, and the success achieved by cybercriminals positions phishing among the most popular computer attacks, and it is both an end and a means to commit other crimes. The website El Consultor del Ayuntamiento [RH1] explains that the most frequently attacked areas internationally are bank and cashier services, online payment gateways, social networks, purchase/sale pages and auctions, online games, company technical support, cloud storage services, public services or companies, messaging services, and false job offers.

Recognizing a phishing attempt is not always easy, but there are small signs that can alert us. The main detail is the sender: if it is an unknown person or company, or anyone with whom one does not maintain certain communication with, it is likely a scam. The same happens when the proposal is so promising that it is almost impossible to reject. If the language used in the message is too generic, almost robotic, it may indicate that it was generated by a computer. The same goes for messages that have bad spelling or grammar.

If we receive a suspicious message or email, the ideal situation it to not open it so as to avoid hacking. However, if you click on the link—because 99% of the time they bring a link—and are asked for a username or password for an account, then all the red flags have been raised.

Personal Data Theft in Cuban Cyberspace

In Cuba, not only have we received the “Are you the one that appears in the video?” messages, but users have also received, via Messenger, texts asking them to write to WhatsApp numbers to request help. People have received emails with requests from refugees (now with the Russia-Ukraine war), minorities who need funds and donations, and even help from a “Nigerian Princess” who needs a secure bank account to transfer funds.

In December 2019, several people reported that the EnZona site had been copied. For 6 days, users mistakenly entered the enzona.org page with an interface the same as the real enzona.net. Their personal data (phone or email and password) was collected and then hackers redirected the users to the real website without them noticing the scam. It is not officially known how many people were affected, nor how much money was lost.

At the beginning of 2022, three citizens who carried out scams through magnetic cards were arrested. Using phishing and other hacking methods, they obtained personal information from third parties, such as email.

These concrete examples of the hijinks that have occurred in Cuba are by no means exhaustive. In fact, some users have reported that even without opening the suspicious video link—let alone entering their credentials and passwords—their information has been sent to third parties.

Although most users are already warned not to fall for these tricks, the ingenuity of troublemakers is a breeding ground for these scams. In addition, the wide spectrum of phishing methods favors cybercrimes. But returning to the subject, is there any legal tool in Cuba to denounce these phenomena in case they are detected in time?

The Data Protection Law project was announced in December 2021 aims to regulate provided personal information both in public institutions in Cuba and in private digital spaces.

The text recognizes personal data as: sex, age, image, voice, gender, identification number, gender identity, sexual orientation, skin color, ethnic, national and territorial origin, migratory status and classification, disability, religious beliefs, ideological principles, marital status, address, medical or health information, and economic-financial, academic, and training data. This information may appear, according to the bill, in registers, files, archives, databases or other means of data processing, whether physically or digitally, of both public and/or private nature.

In article 10, subsection (j) it clarifies that the possession and processing of personal data must be exclusively for lawful purposes. And in subparagraph l) of the same article, it warns that the holder must express his will freely and unequivocally when personal data is being processed and must specify the purpose for which consent is being granted.

Parallel to that is article 12, which states that the owner must be informed both in an understandable and direct manner about the purpose and legalities of the data requested. They have a right to know who is receiving it, whether it is optional or mandatory to provide it, where it is stored, what could be done to it, the consequences of providing it or not, as well as what it done with their data when it’s no longer needed.

But none of these circumstances occur during data theft through phishing, which reaffirms the illegal nature of this phenomenon in Cuba. The problem then is that the hackers are never, or almost never, known, and they may even reside in other countries.

It will be necessary to verify if, whether a phishing or similar attempt is detected from the island, the victims can file a complaint with the authorities and whether or not these complaints proceed. For now, all that can be done is wait for the Law to be approved, which was scheduled for April of this year but has now been delayed to an undetermined date.

Laura Seco-Pacheco graduated with a degree in Journalism in 2018 from the Central University Marta Abreu de Las Villas. She worked for three years at Vanguardia, a provincial newspaper in Villa Clara. Currently, she is a journalist at elTOQUE. She is interested in social, environmental issues, animal protection, and Internet phenomena.

Illustration by Wimar Verdecia Fuentes. Find him on twitter @FuentesWimar

BACK TO NUEVOS ESPACIOS